This is another guest post by our wonderful Curriculum Thinkers Community member, Louise Ferrier. If you find it useful, she’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments here.

Hello Curriculum Thinkers,

We humans are odd little pattern-forming creatures when you think about it. On the one hand we have created the most wondrous of tools and systems that have marked us out as ‘great’. Yet on the other, when entering the staff room, we gravitate to our usual spots or huddle in departments for whole-school training (unless prised apart by a well meaning but universally-loathed ice-breaker)!

We look for patterns; we find comfort in them, rely on them; they are hard-wired in our brains to frame how we view the world.

It is no different with language. I’m reminded of an explanation from the writer Alan Moore of the earliest days of human history, before the written word had emerged, the act of capturing thought on stone or clay would have seemed like a superpower. To turn invisible ideas into visible symbols, to make thinking permanent, is still pretty magical.

This ancient magic is something every student must learn to command; we see evidence that they fear it - how often do we see students stall putting pen to paper as if the permanence of that act could condemn them?

Students need to be taught to build with language; to create their own patterns and build their own blueprints for different types of writing. That is why the power of narrative, the archetypes, the narrative arcs, connections between past, present and future matter to us as teachers. They are the hooks that learning hangs upon and the structures for building effective writing.

Just as stories help students make sense of complex ideas by creating familiar shapes in their minds, structured writing instruction gives them the frameworks to express those ideas clearly and coherently. When we use narrative arcs or conceptual metaphors in our teaching the journey, the obstacle, the resolution, we’re not only engaging students emotionally, we’re also forging neural pathways that support memory and transfer.

In the same way, when we teach students the distinct forms and functions of different types of writing: an argument, a hypothesis, an evaluation, we’re giving them mental scaffolds to hold their thinking. The brain seeks patterns, and writing is one of the most powerful ways to make those patterns visible, and most importantly, replicable.

If we want our students to write well in every subject, we must treat writing instruction like architecture. Extended writing is the grand design, the finished structure, but it can only stand securely when the foundations are deep and the scaffolding is robust. This takes more than the English department’s efforts to achieve; we all play our part in laying those foundations.

Read on to explore how schools in the We Are In Beta community are using:

Vocab instruction

Building Sentences

Long answer exam questions

AI as a tool for quick modelling

Whole Staff Training

Writing like a…

1. Vocab Instruction

Vocabulary instruction is the raw material of the writing foundations: a student cannot “write like a scientist” or “argue like a historian” without first acquiring the specialist language of those disciplines and the tier 2 academic language to support it.

We know that the vocabulary gap starts early. Closing it so that students can both read and write confidently requires a strategy for explicit vocabulary instruction in all subjects.

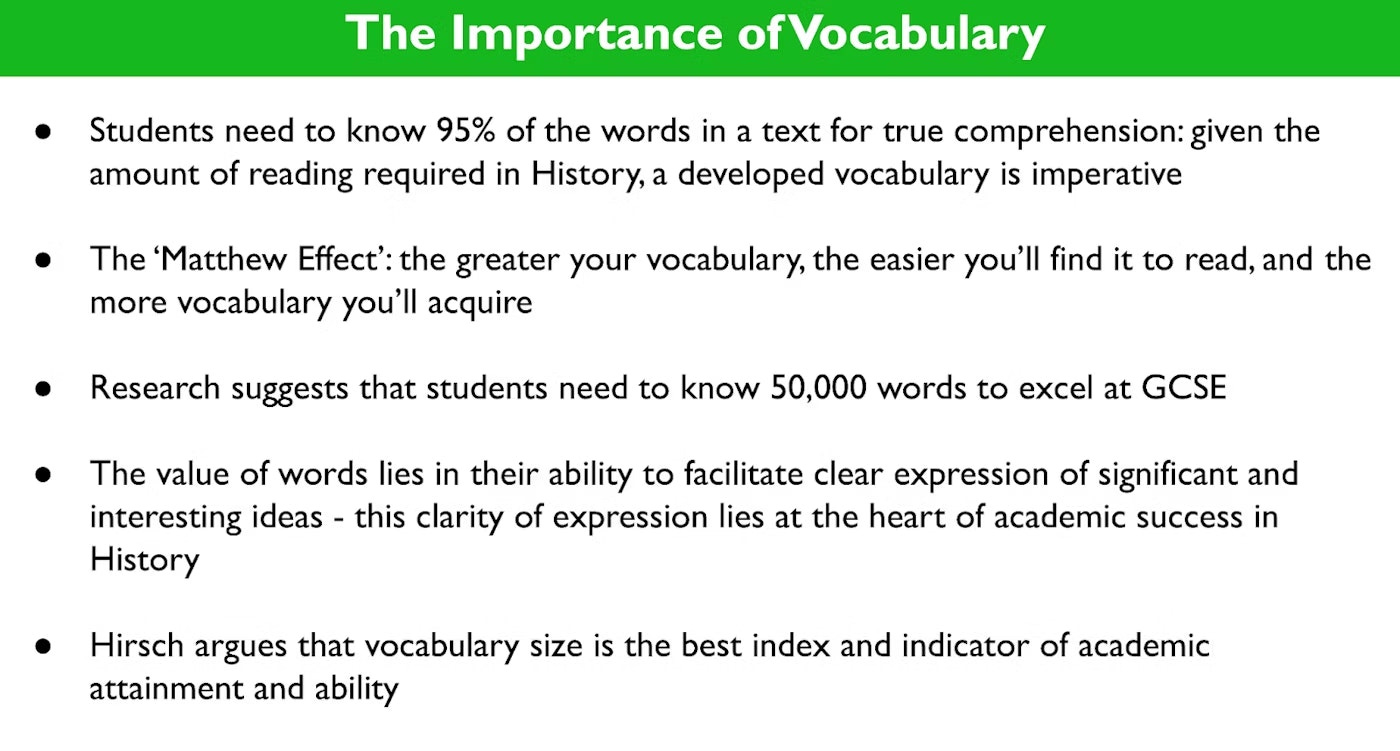

The Whitefield School made explicit vocabulary instruction a whole-school focus, recognising the importance for all subjects as seen in the slide below:

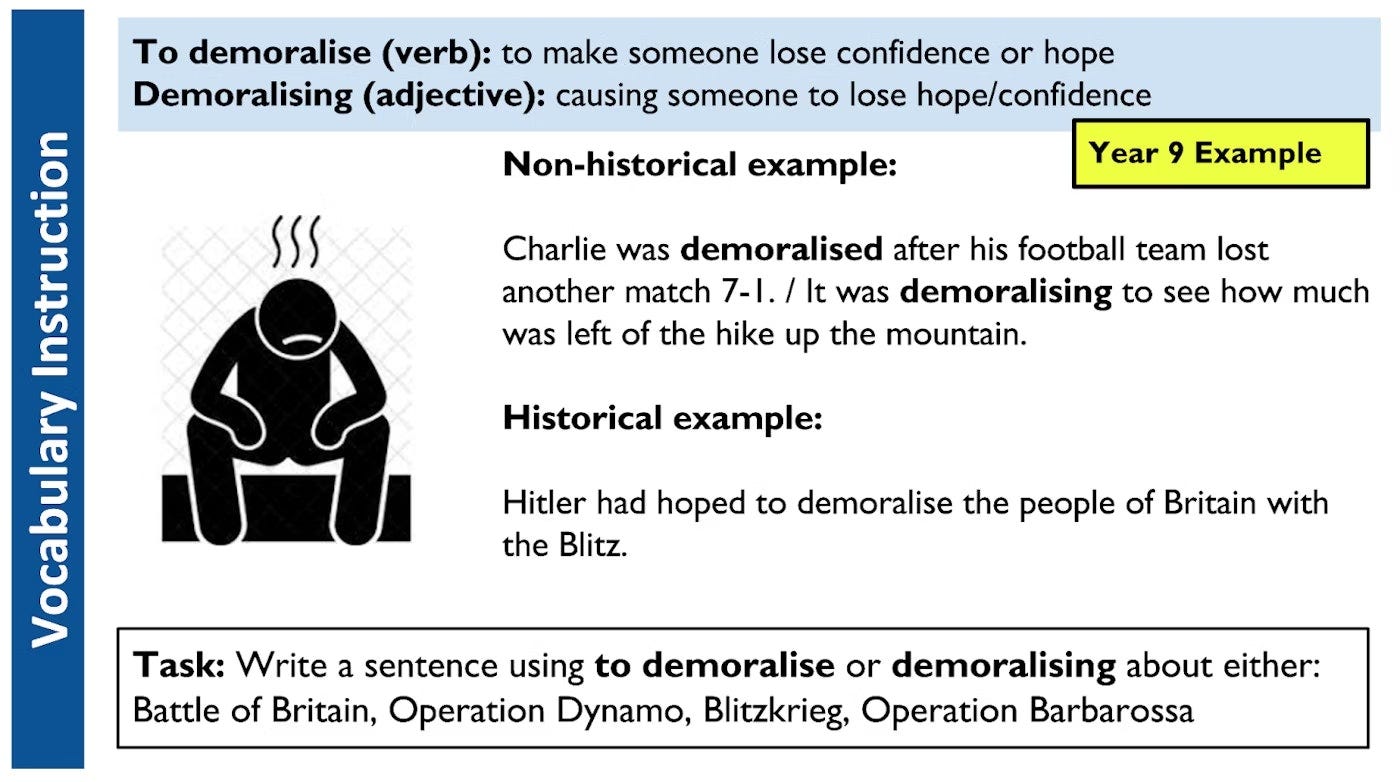

They focused on Tier 2 and 3 vocabulary to build an academic foundation and used strategies such as the Frayer model which is a form of graphic organiser used to demonstrate a word’s meaning and usage. They also utilised subject-specific models and tasks such as the history example featured below.

Watch the full presentation here.

2. Building Sentences

Whilst being stuck at the ‘building sentences phase’ for too long can hinder higher attainers, there is no doubt that sentence building and sentence starters have their place in our scaffolding repertoire.

Explicit instruction on how to approach and recognise units of meaning within a sentence and to build on them to be both efficient, accurate and effective can be achieved in any subject. It starts with recognising what are effective structures within our subjects and giving students space to emulate, practise and then build on those structures.

What I really enjoyed about the presentation from the English department of Les Quennevais School, was the adaptability of the 'think phrases' to all language based subjects. Students were able to practice, after explicit instruction of how units of meaning are built, creating meaning and controlling meaning using a variety of tools like the think phrases listed below.

Watch the full presentation and access the resources here.

3. Long Answer Exam Questions

Extended answers are a challenge across subjects because they demand both subject knowledge and writing stamina. Practise, practise, practise is the key. Without consistent opportunities to practise, students often struggle to organise and develop their ideas with clarity.

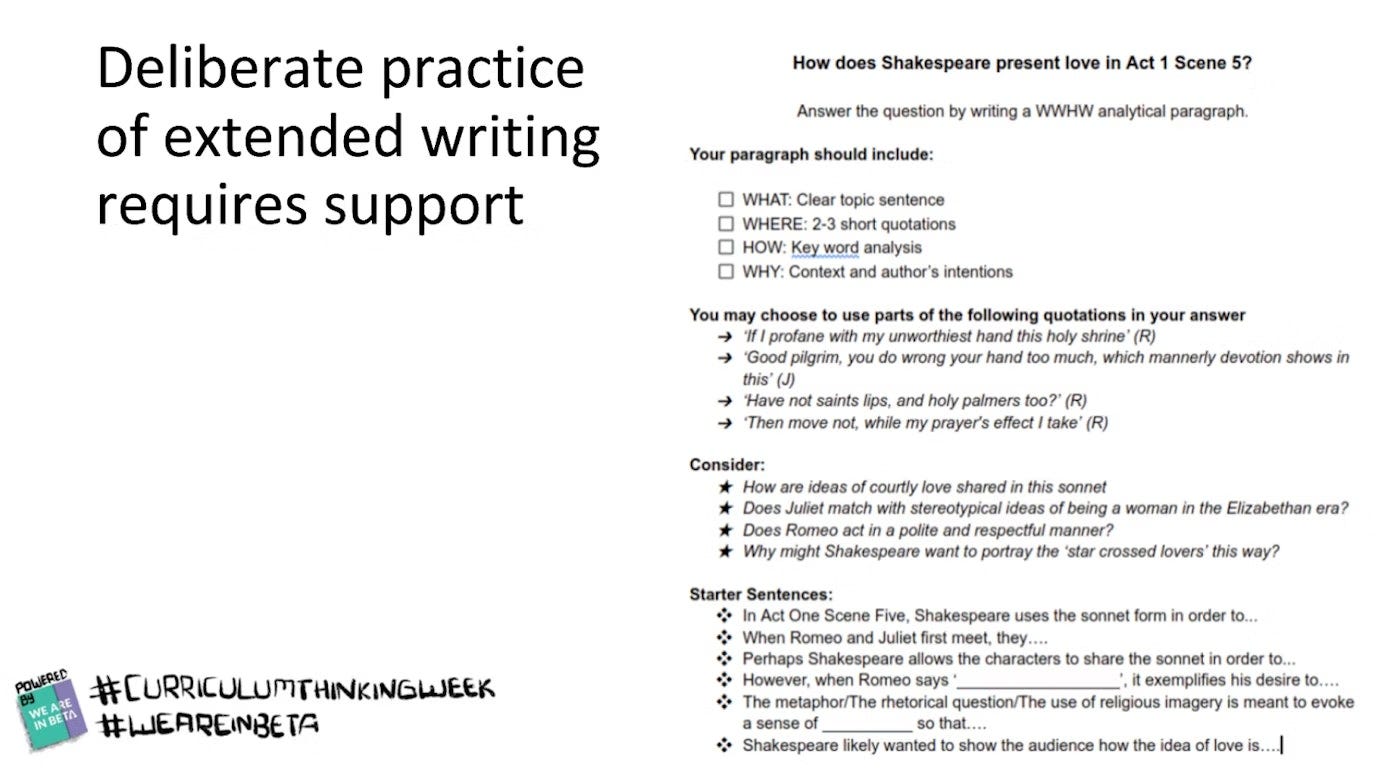

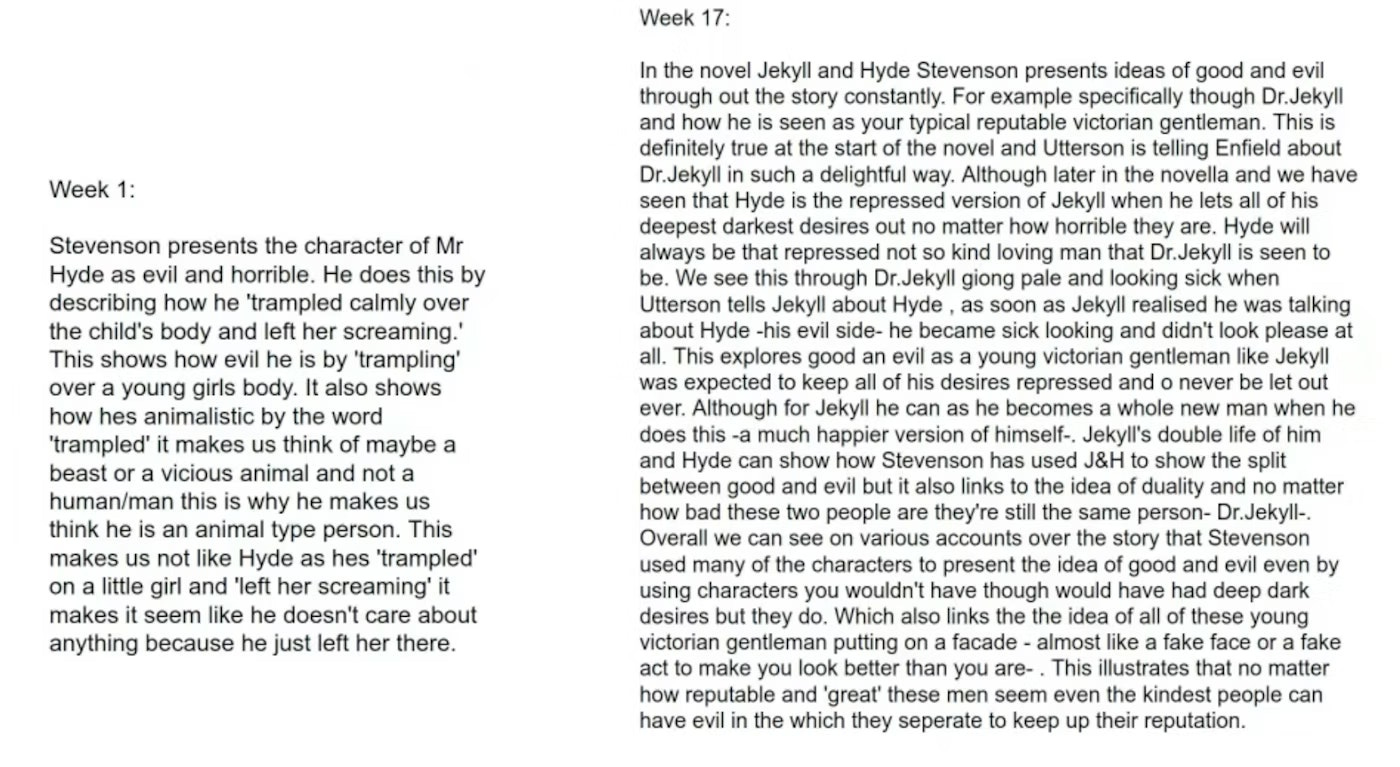

For Wheatley Park School's English department, home learning is used to try and build stamina for extended writing tasks. They model in their presentation, a system of building up to extended writing using home learning tasks that begin with retrieval quizzing and culminate in writing practise. The improvements they have seen are demonstrated in the example below:

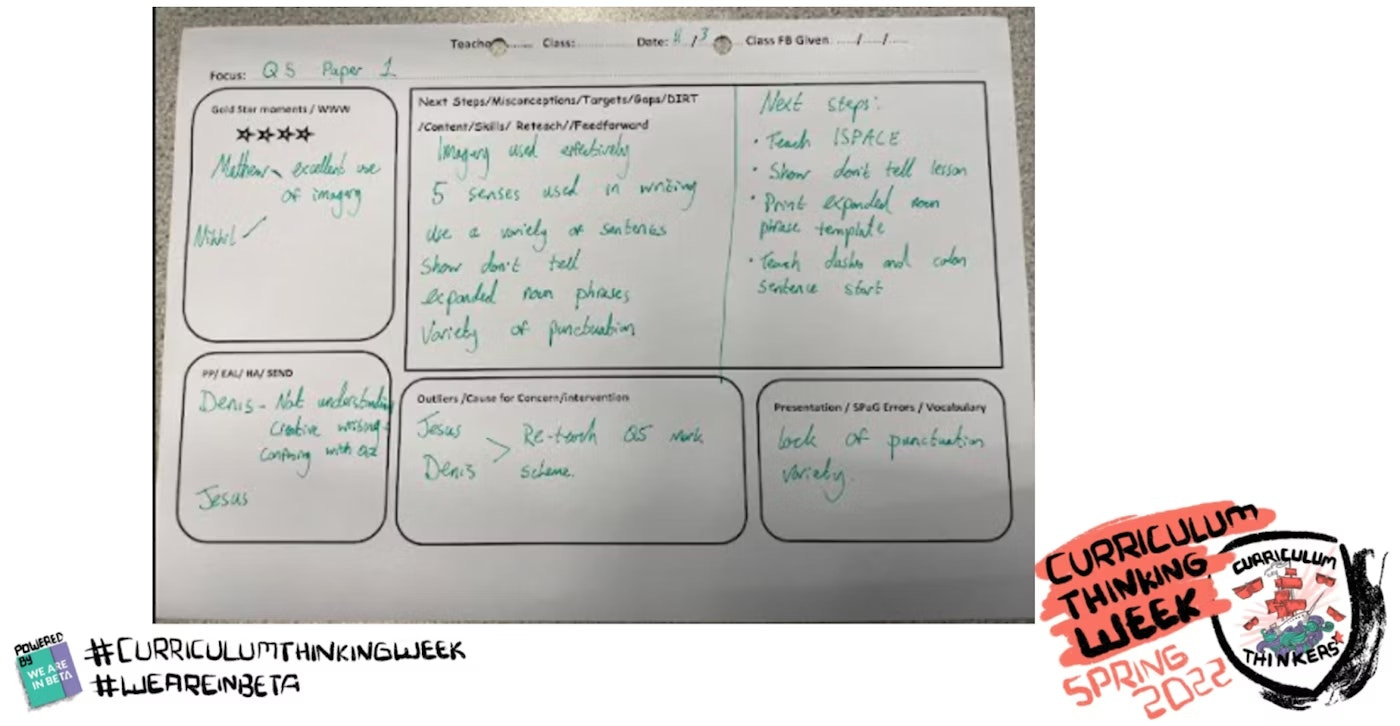

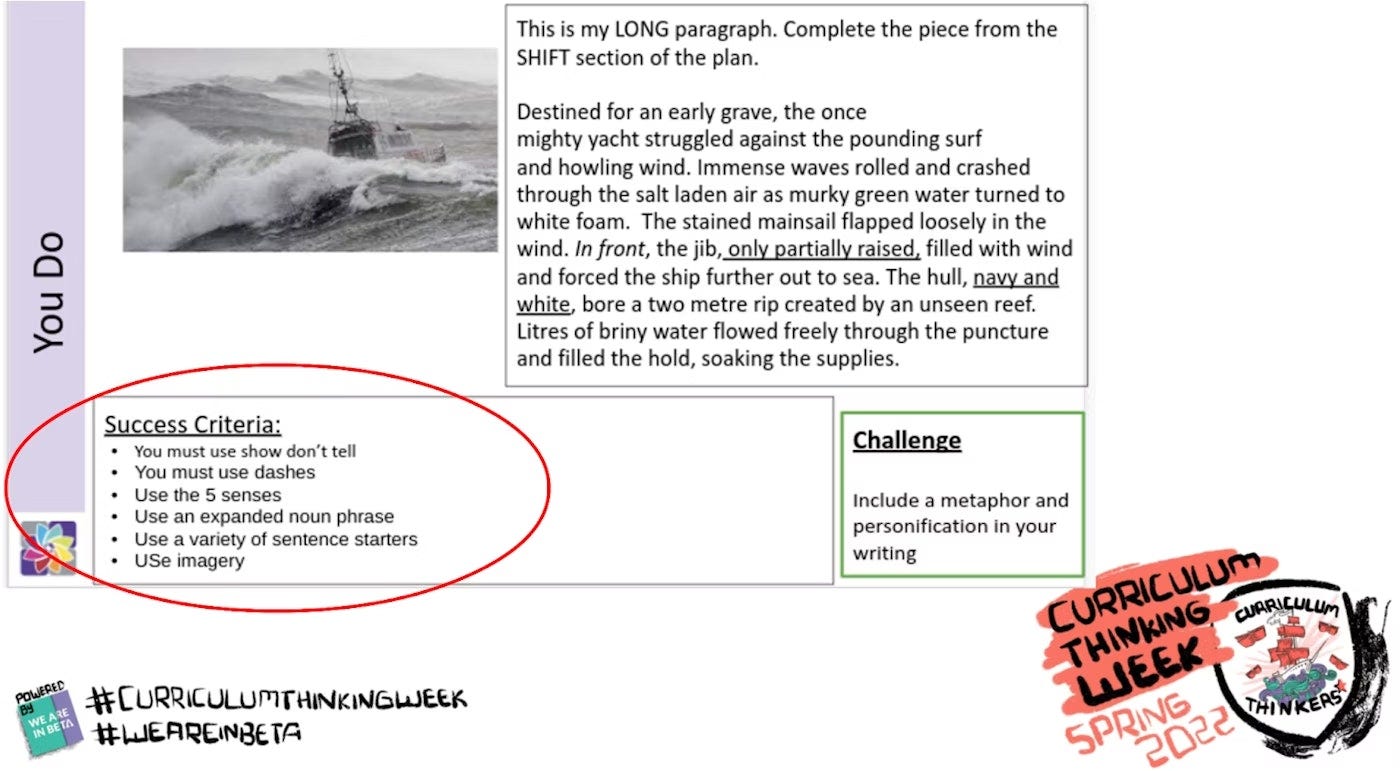

The feedback methodology used at Kingsley Academy to support EAL writing resonates with writing improvement for all students. Writing tasks have very clear success criteria and feedback specificity is targeted to ensure that any issues are addressed.

There is an expectation that there will be an opportunity for the target to be practised in near-future work or that the student will return to piece if it has been missed:

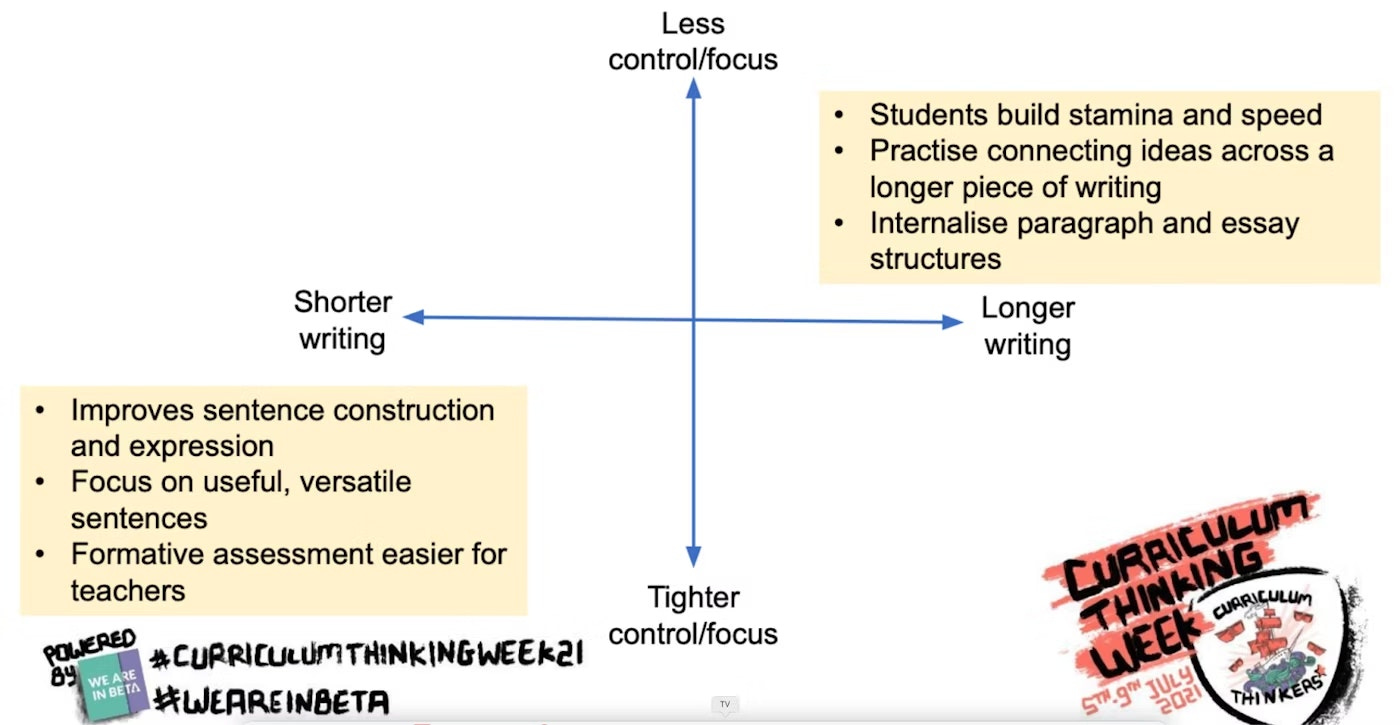

Greenshaw High School’s English Department noticed that students were struggling with extended writing and took steps to develop stamina and resilience to be able to tackle long-form answers. They understood that there is a place for the shorter, structured pieces of writing that develop writing skill, but at KS4 they wanted students putting those skills into practice and ensuring that students got a balance between the two.

Watch the Wheatley Park presentation here.

Watch the Kingsley Academy Presentation here.

Watch the Greenshaw High School presentation here.

Some resources and recordings are only available to paying members of the Curriculum Thinks Community who can:

learn from hundreds of recordings covering every aspect of curriculum development across 20 subjects

download 2000+ resources - both whole school and subject specific

access 700+ academic related policies, plus analysis of them, from successful schools - T&L, assessment, homework and more.

Not a member? Get a trial here

4. AI Models

Producing models for writing is a fundamental part of the process of improving writing whether that's to demonstrate a specific skill or to produce a model that students can imitate. For producing quick examples, such as generating varied sentence structures, or demonstrating a model paragraph in seconds, AI can save precious teacher time and provide instant clarity for students. Used well, it has the potential to accelerate writing instruction, but not as a substitute for skilled teaching.

AI can also allow us to tackle writing issues in a responsive way. For example, the following AI prompt: ‘produce two model GCSE History 12 mark answers on the challenges Henry VIII faced to the annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon - one answer with noun appositive phrases and one without to show the differences in detail’ produced two full answers in seconds including these example paragraph openers which could allow students to see and then imitate using appositive phrases to add more detail efficiently:

Example 1: ‘Another major challenge was Catherine of Aragon’s own resistance to the annulment.’

Example 2: ‘Another major challenge was Catherine of Aragon’s personal defiance, a dignified and devout queen determined to protect her marriage and her daughter’s legitimacy.’

The ability to be very specific in our demands of what a model includes could really help our responsive teaching of writing in real time.

Developing teacher efficiency in using AI also requires time and CPD. The NFER and EEF have recently completed a research project with KS3 science teachers and found that, on average, teachers using AI in planning save over 30% of planning time a week - not to be sniffed at.

Check out the recent summary of DfE’s ‘Generative artificial intelligence (AI) in education’ here. If you are using AI to support the teaching of writing in your subject, be sure to post about it in the community.

5. Whole Staff Training

This is potentially an area of contention but none of us are immune to SPaG slips and for some of us, we have not had a refresh of literacy training since we left school ourselves.

According to the National Literacy Trust far fewer teachers enjoyed writing (56.2%) than reading (85.8%) in their 2023 survey. While 9 in 10 (92.1%) teachers across all subjects thought it was their job to teach literacy.

Writing quality matters. It is a life skill. As professionals, we have many tech tools at our disposal to mask any of our own literacy foibles but in order for us all to be effective teachers of literacy, we really do need to know our onions (or more accurately: our semicolons, noun appositives and verb agreement).

Getting teachers excited about this as an uncontextualized CPD exercise is unlikely to end well (I did have a colleague many moons ago who nobaly adopted an entire wall in the staff room to grammar rules - a hilarious nod to the many assemblies with abused apostrophes and homonyms but risks giving all English departments the nickname of ‘grammar-police’).

Debra Myhill et al (2021) in their paper ‘Writing as a craft: Re-considering teacher subject content knowledge for teaching writing’ exposed:

“...an empirical silence on what constitutes teacher knowledge for writing.”

They found that:

“Professional understanding of subject content knowledge influences practice, and, as a recent systematic review of teachers as writers’ highlights, there is value in pre-service and in-service programmes developing teachers’ conceptions of writing and sense of self as writers”

So what might CPD exploring ‘conceptions of writing’ look like? This is where Myhill’s paper is really interesting. They dissected the practise of accomplished writers into five themes that form subject content knowledge for writing:

Writing Process

Being an Author

Text-level Choices

Language Choices

Reader–Writer Relationship

With this in mind and the EEF advice of having clarity within your subject area of what the ‘rules of writing’ are in each discipline is a good place to start. Having a shared understanding and a shared language for each of Myhill’s five themes helps to determine that clarity. Which leads us neatly on to…

6. Writing like a…

Writing like a geographer, historian, scientist, literary critic and so on is… complex to say the least. It is the culmination of all of the subject-specific vocabulary work, sentence scaffolds, pastiche of expert writing and a multitude of practice.

Disciplinary literacy is where using reading and writing together comes into its own. In the EEF’’s ‘Improving Literacy in Secondary Schools’.

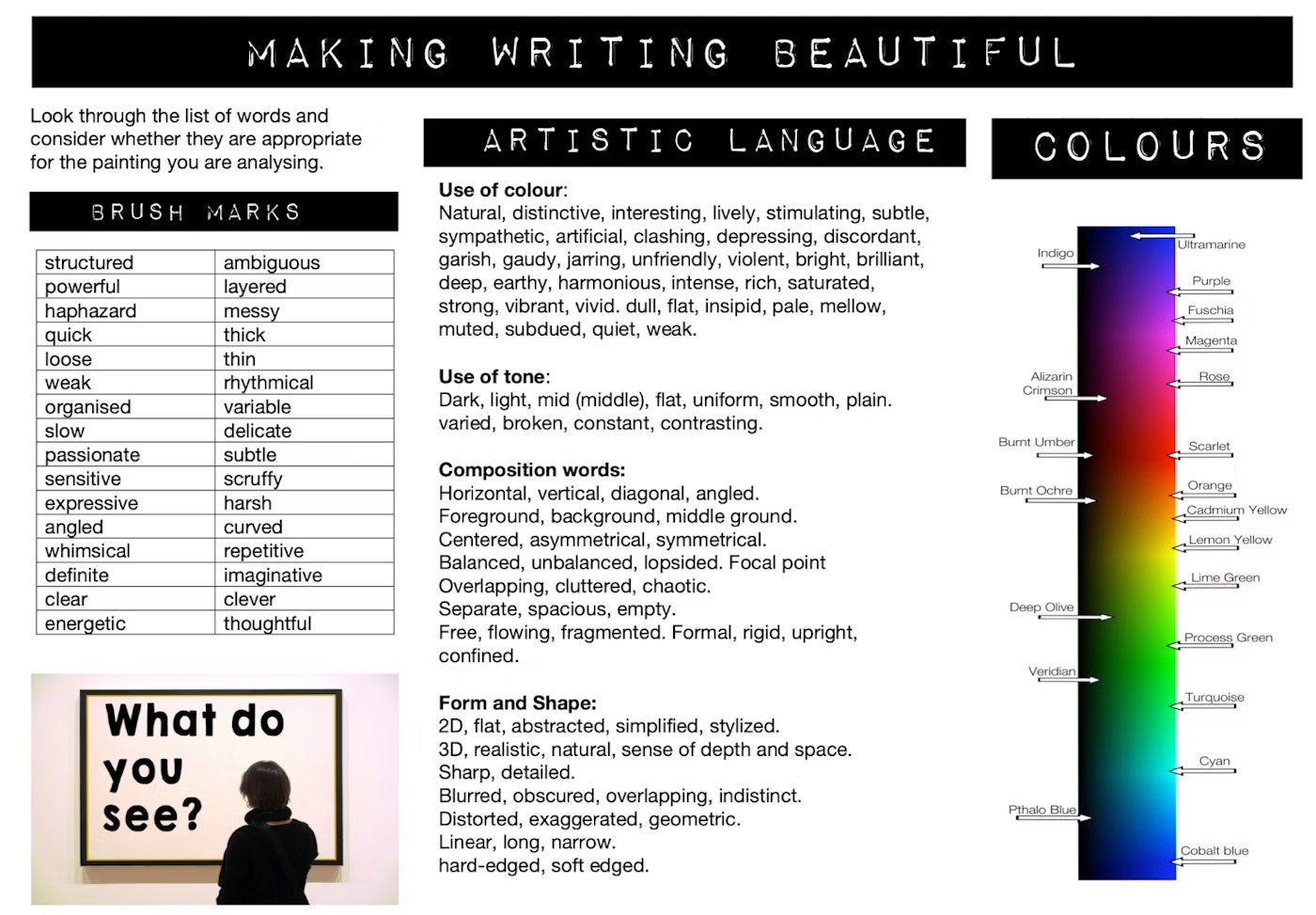

To explore the concept of writing like an ‘expert’ I want to share with you a really interesting presentation from the art department of Les Quennevais School where we see the whole journey of developing Yr7 students to write like art critics in one place.

Each stage is completely replicable by other subjects. For me, the excitement of using really high-quality writing in the examples offers opportunities for teachers to get excited about sharing challenging but interesting writing with our students.

The journey starts with the vocabulary knowledge organiser:

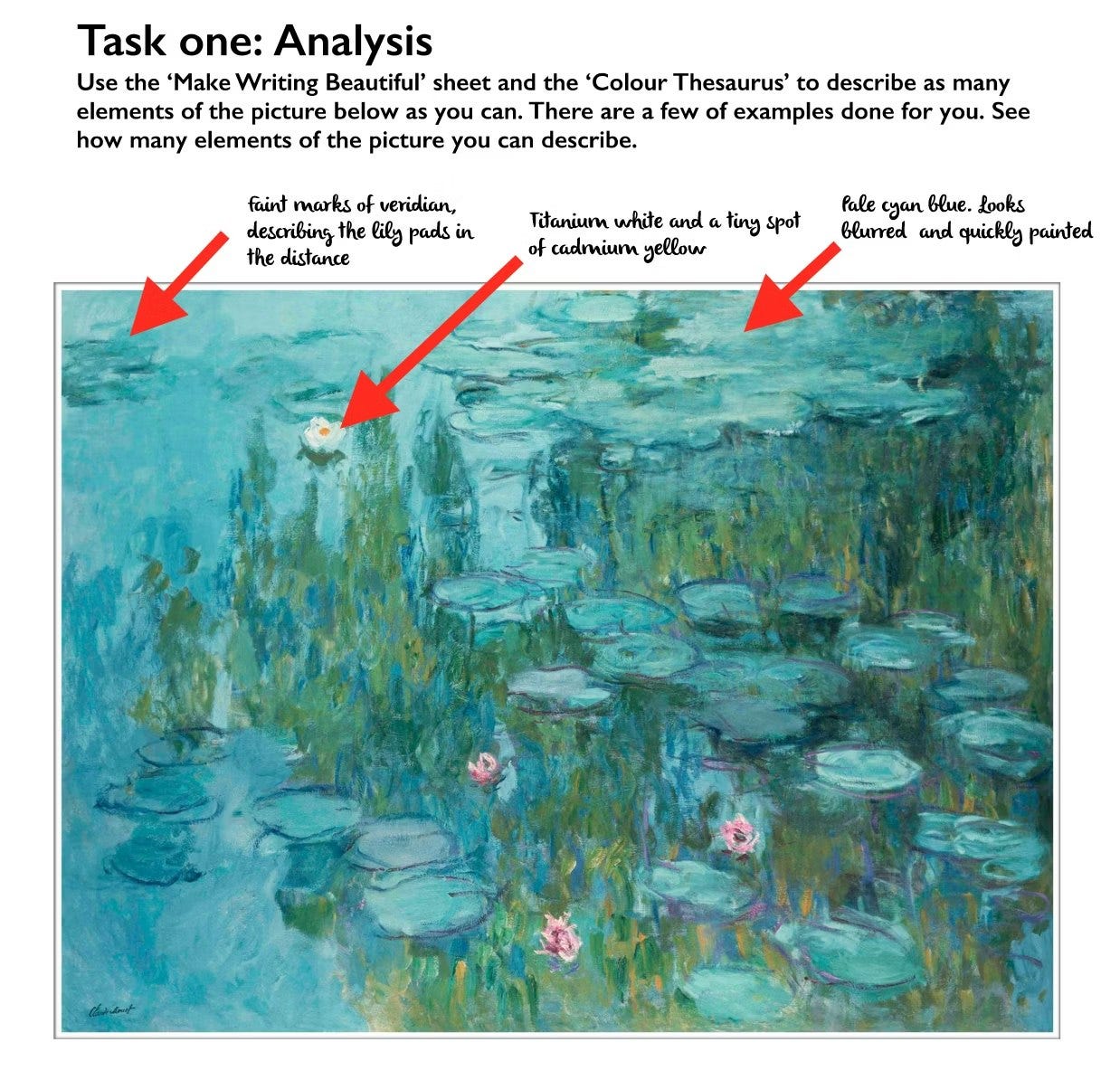

The vocabulary is then applied within context:

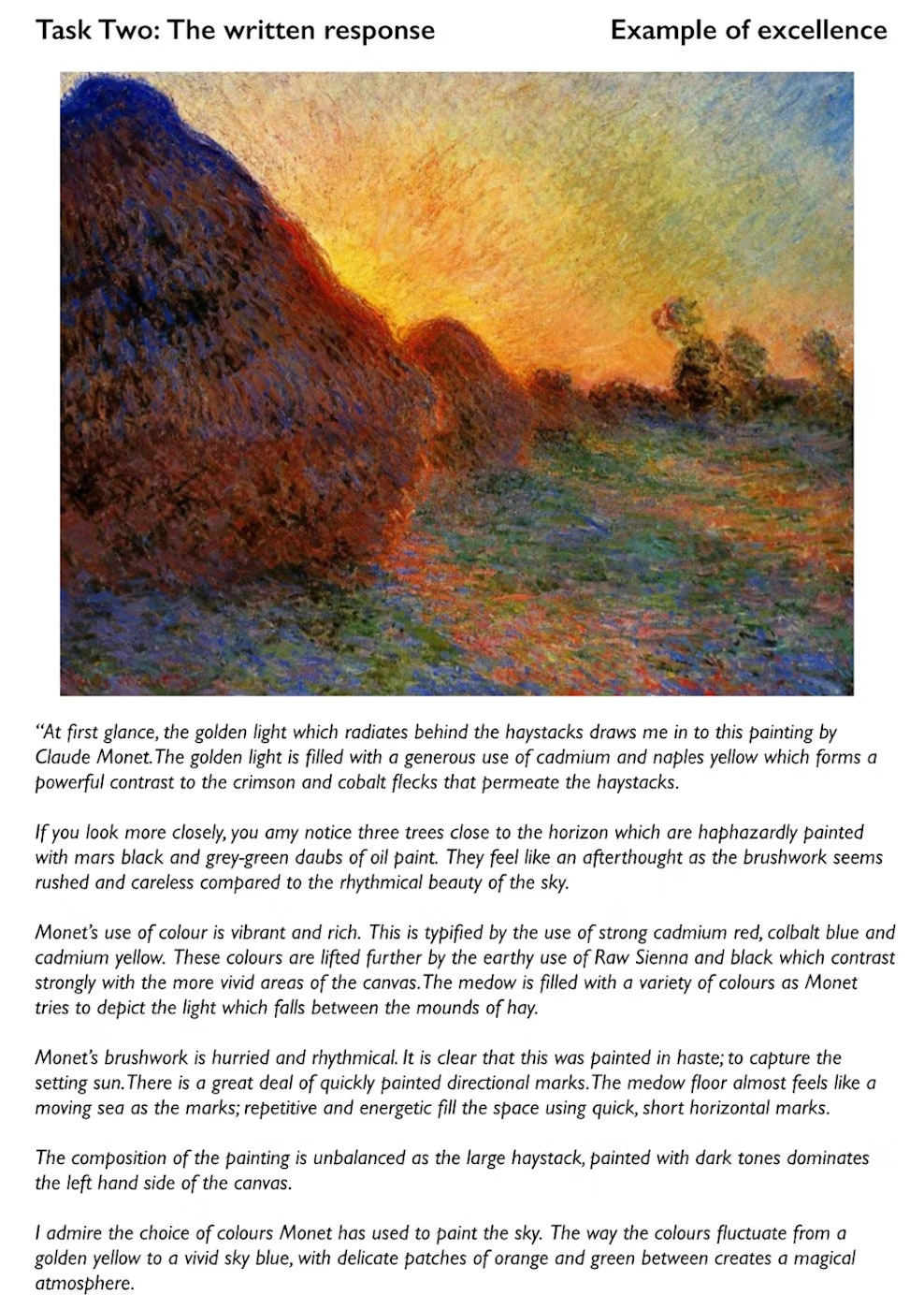

An example of writing like an expert is then shared and deconstructed for its features with the class:

Scaffolded sentences begin the journey of writing like an expert:

As students grow in experience with this model, the scaffolds can be removed and students can be encouraged to build their own writing style.

Watch the full presentation here.

Next week we share subject-specific examples of writing improvement in action.

Sent with ❤️ from the Curriculum Thinkers Team at We Are In Beta

Might be of some interest to you. https://thatpovertyguy.substack.com/p/the-c-word-part-1